Where the Suburbs End

October 8, 2021 | The New York Times | By Conor Dougherty

“More luxury at lower cost.” The pitch rolled across the cover of a brochure that introduced thousands of aspiring homeowners to Clairemont Villas, a San Diego subdivision that promised new homes in a world without trade-offs.

“Private and protected.” “Beauty and convenience.” A single-family house in a quiet suburb — but just a few minutes’ drive from new schools and a new shopping center along with downtown and the beach.

It was a California fantasy. Over six colorful pages the brochure sold buyers on an indoor-outdoor lifestyle where the living room opened to a yard and children played behind a redwood fence.

The fairy tale ended with the map to an address on Clairemont Drive. That’s where a row of model houses sat bunched up on a corner, waiting to be walked through.

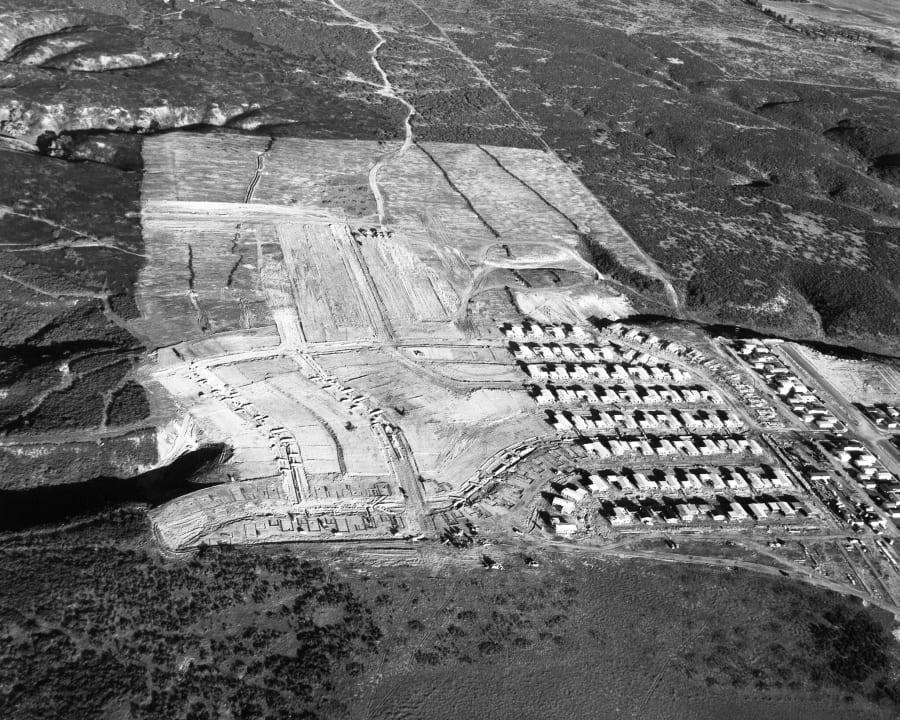

Sixty-five years later, Margie Coats, 79, still remembers the tour. Her father drove the six of them — two parents, four sisters — to a weekend showing where in her teenage naïveté she asked a salesperson if the furniture was included. The family paid $13,250 for Lot 118 and a year later moved into 5120 Baxter Street. This was in 1957, back when the surrounding Clairemont neighborhood was booming with new subdivisions and mass-produced suburbs were still a national experiment.

Neighbors in Clairemont Villas picked from a selection of four Craftsman houses that had the same cabinets, similar floor plans and an option to add a washing machine. (Clothes still had to be dried on a line.) Most of the residents were young families with parents who worked a mix of trade and professional jobs that had roughly the same paychecks.

Ms. Coats’s father, Paul Shannon, was an aeronautical engineer who had left the Navy to work in private defense. This afforded them the relative affluence of a four-bedroom house with a yard that was bigger than any of their neighbors’. It became the block’s social center.

“That was where everybody congregated on the weekends,” Ms. Coats said. “People would pitch in: Somebody would bring beer, somebody would bring hamburgers, somebody would bring hot dogs, and we would just all gather.”

Ms. Coats has not ventured far since: She moved about 40 feet away and has spent almost her entire adult life living across the street from her childhood home. Her former yard is the first thing she sees whenever she leaves the house, a view that allowed her to follow the daily progress of a construction project that over the past few months transformed 5120 Baxter from the suburban vision of the 1950s to a projection of California’s tighter, taller future.

In June, as Ms. Coats told me about the house and the neighborhood from the doorstep of her bungalow, she gazed toward a fresh foundation that had entombed the back half of Lot 118 in concrete. Over the next few weeks, a construction crew erected a two-story building that filled in a green rectangle from the Clairemont Villas brochure. A few feet away, the original four-bedroom house was loudly gut-renovated into a pair of apartments.

Margie Coats in front of her home in the Clairemont neighborhood of San Diego. Sandy Huffaker for The New York Times

When the workers head to their next job this month, they will leave what amounts to a triplex rental complex on the type of lot that in the seven decades since Ms. Coats’s family moved in had been reserved for single-family houses. It’s part of a push across California and the nation to encourage density in suburban neighborhoods by allowing people to subdivide single-family houses and build new units in their backyards.

Dan Logue, 60, a teacher who lives on Baxter Street, said he was excited about the project, and backyard houses generally, because they allowed homeowners to develop their own land. (“Neighborhoods change as people die off, and that’s just reality.”) Ms. Coats was so-so. She said she was worried about less parking but also about San Diego’s housing problem and hoped the new units would do some good. (“I’m not going to go down to the City Council and beat my head against the wall and say, ‘No, no, no.’”)

Cary Gross, 63, who owns a tile company and lives next to Ms. Coats, is against it. He invested on a single-family block 25 years ago with the expectation that it would stay that way. “They say they’re doing this so everyone can have the American dream,” he said. “But what about the American dream of living in a single-family neighborhood?”

The house at 5120 Baxter Street has been home to three families and contains any number of stories. The one I’m going to tell you is about the house’s place in California’s spiraling affordable housing crisis and the state’s efforts to halt it.

The suburban dream that Ms. Coats’s family bought into has become the American housing system. Reforming it is key to any number of existential problems, including reducing segregation and wealth inequality or combating sprawl and climate change (transportation accounts for about a third of the nation’s carbon dioxide emissions). But the process will be long and difficult, as single-family neighborhoods are America’s predominant form of living and homeowners broadly enjoy them.The implications go way beyond geography. The America that prevailed when Ms. Coats’s family of six moved to Baxter Street was a more middle-class country, where women had about 3.5 children on average. Today inequality is much starker, and the fertility rate has been cut in half as adults remain single longer and have fewer or no children after they pair up. Members of the millennial generation continue to lag their parents in homeownership, and 20 percent of U.S. households are multigenerational — up from 12 percent in 1980 — as families grapple with the cost of living.

In other words, the pressure to remake neighborhoods like Clairemont is due not to some sudden shift in what people want out of a home but rather to the sweeping social changes that have already played out inside them. As the Columbia University historian Kenneth Jackson wrote in “Crabgrass Frontier,” his seminal history of America’s suburbs: “No society can be fully understood apart from the residences of its members.”

A Very Different California

The Clairemont neighborhood in 2021. Roger Kisby for The New York Times

Clairemont Villas in 1955. San Diego History Center

When Ms. Coats moved into the Baxter Street house, a family needed right around the area’s median income to afford the $82 monthly mortgage payment — the definition of middle class. Today a typical Clairemont home costs $850,000, up 30 percent from 2019. A family would need to make about double San Diego’s median income to afford one, according to Redfin, the real estate brokerage. And it wouldn’t be a new place.

That inflation all but defined the lives of the Reece family, which moved into 5120 Baxter a decade after the Coats family moved out and stayed there until last year. John Reece was a retired master chief petty officer in the Navy who spent five years saving for a down payment by living in a trailer park with his wife, Barbara, and baby daughter, Patricia. The Reeces entered the house in 1976 as renters and bought it two years later.

Patricia Reece would spend most of her adult life struggling to leave for a home of her own. She moved into and out of Baxter Street several times while she raised kids and completed college. In 1993, the year a house down the block from Baxter Street sold for $117,000, she and her husband at the time moved to Pennsylvania with a plan to emulate her parents’ strategy of saving money in a trailer. (“We were like, ‘Hey, my parents started in a trailer — we can get our trailer and make this happen.’”) When they returned two years later, the same house was on the market for $168,000, Ms. Reece said.

California home prices have only risen since, resulting in a worst-in-the-nation affordable housing crisis. Juxtaposed against large numbers (a median price over $800,000) and zany stories (sales $1 million above the asking price) are the scenes of abject misery that unfold in the daily lives of the 100,000 souls who live along its freeways and streets.

The root of all this is a decades-old housing shortage. Since the mid-1970s, when home prices began outpacing wages, planners and economists have argued that California’s housing problems will persist as long as it remains one of the hardest places in America to build shelter. Nevertheless, city councils and the State Legislature more or less ignored this advice until a few years ago.

Faced with ballooning home costs that even a pandemic couldn’t tame, politicians from both parties now routinely talk about the state’s and nation’s affordability problems in terms of a lack of homes. The debate is about where and how to build new ones.

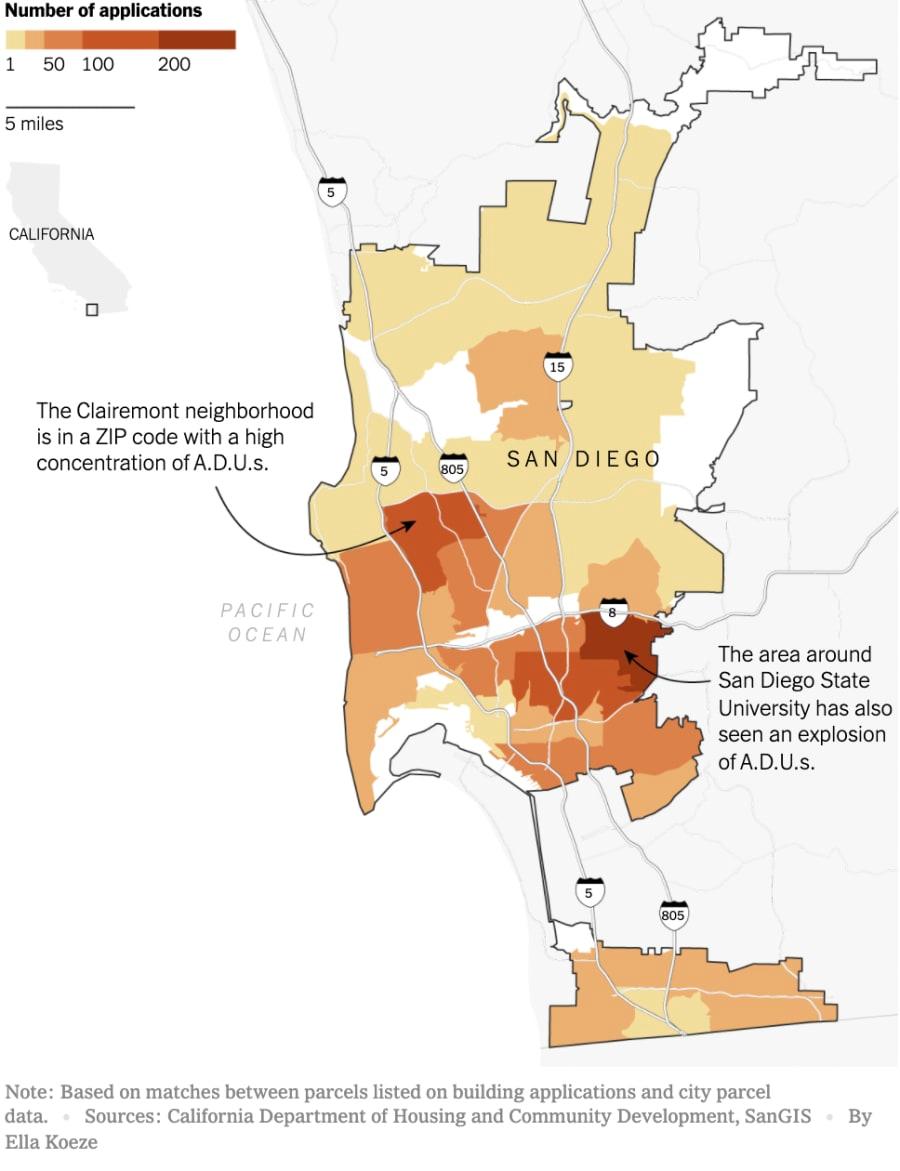

Buildings Are Cropping Up in San Diego Backyards

Building applications for accessory dwelling units in San Diego from 2018 through 2020, by ZIP code

Across America, housing is for the most part built in one of two familiar ways. The first is when acres of fields outside the urban center are turned into wide streets and cul-de-sacs named after trees. The second is when a developer descends on an already urbanized neighborhood and, after donating to a few campaigns and feuding with anti-gentrification activists, builds a glass condominium tower or high-rent apartment building.

In the vast zone between those poles lie existing single-family neighborhoods like Clairemont, which account for most of the urban landscape yet remain conspicuously untouched. The omission is the product of a political bargain that says sprawl can sprawl and downtowns can rise but single-family neighborhoods are sealed off from growth by the cudgel of zoning rules that dictate what can be built where. The deal is almost never stated so plainly, but it is the foundation of local politics in virtually every U.S. city and cuts to the core of the country’s deepest class and racial conflicts.

And now it’s being torn up. The loudest rip came last month when, two days after surviving a California recall election, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed Senate Bill 9. By legalizing duplexes statewide and allowing people to subdivide single-family lots, S.B. 9 effectively ended single-family zoning in a state of 40 million whose identity is predicated on the suburban idyll.

But that was just the latest in a yearslong effort — one mirroring efforts around the country — that ushered in dozens of state housing laws that streamline construction of backyard units, require cities to plan for higher-density development and strip them of power if they fail to comply.

When you add S.B. 9 to earlier rules for backyard units, California has paved the way for some 2.5 million new housing units — about 25 years’ worth at the state’s current pace of building — in existing single-family neighborhoods, according to an analysis by the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at the University of California, Berkeley.

“These laws have opened up entire communities that had been largely walled off,” said Ben Metcalf, managing director of the Terner Center. “Even if it starts slow, we are solidly on a path to a very different California.”

Clairemont is at the center of this retrofit. The neighborhood is a classic post-World War II suburb built around curved streets and strip malls. In the ’50s it was promoted as a hamlet outside the bustle. Now it is centrally located, between downtown San Diego to the south and the northward cluster of biotechnology companies expanding around the University of California, San Diego. The city is recasting the area as a transit hub where people live closer together and commute via a $2.1 billion expansion of the San Diego Trolley.

John Reece was 82 and stricken with Parkinson’s disease when the California Legislature began its housing push in 2016. Patricia Reece was in her 40s with three children and had returned to Baxter Street once again, this time from Missouri, where she had finally bought a home but was foreclosed on during the financial crisis. She had a doctorate and was working as a psychologist, but saving for a down payment in San Diego still felt like an exercise in futility.

What would they do when Mr. Reece passed on? The question lingered in the background until 2019, when the inevitable happened and Ms. Reece inherited the property. Low on savings and heavy on student loans, she did what middle-class Californians do when they want a bigger home and need to pay down debt: She sold her parents’ house and moved to Texas.

“I could get money underneath my belt so that my kids could get their educations underneath their belts,” Ms. Reece said. “In California, we couldn’t do it.”

A year later, 5120 Baxter passed to a limited liability company operated by Christian Spicer, a longtime home-flipper looking to get in on the backyard boom.

The Bloody Shirt

Christian Spicer discovered accessory dwelling units after a fortuitous encounter with a city inspector, and it led to a new line of business. Sandy Huffaker for The New York Times

Christian Spicer, 34, began his real estate career in the throes of the Great Recession, when millions of families were being foreclosed on and investors were buying homes on courthouse steps. He was the guy who showed up at people’s doors to tell them, in the nicest way possible, that their property belonged to someone else and that they had to work out a rental agreement or find another place to live.

Mr. Spicer is a mellow presence who speaks in a voice that could get him cast in a movie about people who like to get high and surf (“I’m definitely on the chill vibe of things”). But he is also 6-foot-3 and 250 pounds. The home buyers he worked for during the recession thought this made him a good candidate for house calls — in case anyone got mad, which of course people often did. Most of the time this manifested in a profane version of the words “screw you,” but once someone stabbed him in the arm with a pen. He went to his next appointment in a bloody shirt.

“It didn’t feel great,” Mr. Spicer said of the job. “The fun part was now I got to go in and turn the unit. I got to decide the color of the cabinets and clean it up, put the flooring in, and I’d have this product I was proud to go and lease.”

His professional life has ever since been dictated by a cold calculation of which sorts of properties are generating the best returns for his investors. He was part of the national frenzy to turn foreclosures into single-family rentals. After the housing bust, when the economy and the real estate business improved, he shifted toward house flips and “value-add” apartment deals, a euphemism for buying a run-down complex, clearing out the tenants, then renovating and raising the rent.

It’s an equation of risk versus profit: In a world in which the need for housing is high but it’s hard to build, upscaling properties is a safer way to make money than trying to develop new ones.

Mr. Spicer discovered backyard units after a serendipitous encounter with a city inspector. The inspector came by to check the electrical work at a house he was renovating (and planned to flip), then busted him for tearing out the kitchen without a permit. Mr. Spicer had to pay a year of extra mortgage payments while the work was stalled for city approval. During the wait, a drafter he had hired suggested that he convert the detached garage into a separate unit, which would increase the purchase price.

It was so easy to build and the permitting so fast, Mr. Spicer said, he followed the returns to a new line of business. Now, for the first time in his career, he is trying to make money by building new housing instead of by making existing housing more expensive.

Delivering Apartments on a Truck

The accessory dwelling unit at 5120 Baxter Street. Sandy Huffaker for The New York Times

During a visit to some of his projects, Mr. Spicer drove around town in a dusty black Tesla that had uncashed checks scattered around the center console. Dressed in shorts and a T-shirt, he played a version of an HGTV host, taking me through recently purchased houses and using a mix of imagination and finger points to explain how, with a wall here and door there and two units back there, the rental value could be multiplied several times over.

Instead of hunting for easy house flips, Mr. Spicer said, he’s on the lookout for homes on abnormally large lots with a flat, neglected yard that is primed to start building on. Anything with a pool is out of the question, he said. A home with an elaborate garden can work but costs extra to rip out.

“If it’s all dirt back there, that’s the golden ticket,” he said.

Mr. Spicer’s turn of fortune was a byproduct of California’s efforts to fill its housing shortage. Over the past five years the Legislature has passed a half-dozen laws that make it vastly easier to build accessory dwelling units (A.D.U.s) — a catchall term for homes that are more colloquially known as in-law units and granny flats.

Cities have lost most of their power to prevent backyard units from being built, and state legislators have tried to speed construction by reducing development fees, requiring cities to permit them within a few weeks and prohibiting local governments from requiring dedicated parking spots. In contrast to the battles over S.B. 9 — this year’s duplex law, which was branded a bill of “chaos” that would “destroy neighborhoods” and be “the beginning of the end of homeownership in California” — the A.D.U. laws passed with no comparable controversy.

“‘Granny units’ doesn’t sound intimidating,” said Bob Wieckowski, a state senator from the Bay Area city of Fremont, who has passed three A.D.U. bills since 2016.

Last year, San Diego’s City Council voted unanimously to expand on state law by allowing bonus units, sometimes as many as a half-dozen per lot, if a portion are set aside for moderate-income households. Development has exploded on cue.

California cities issued about 13,000 permits for accessory units in 2020, which is a little over 10 percent of the state’s new housing stock and up from less than 1 percent eight years ago. The effect is already visible throughout Southern California: four-unit buildings rising behind one-story bungalows; prefabricated studio apartments being hoisted into backyards via crane; blocks where a new front-yard apartment sits across the street from a new backyard apartment down the way from a new side-yard apartment.

In response to the new legislation, entrepreneurs have started a host of companies that specialize in helping people plan, design and build backyard units and the coming wave of duplexes. Venture capitalists have put hundreds of millions of dollars into start-ups like Abodu, which is based in Redwood City, Calif., and builds backyard units in a factory, then delivers them on a truck. Until recently, their business was driven by homeowners building A.D.U.s on their property. But over the past year there has been a surge in interest from upstart developers like Mr. Spicer, according to interviews with planners, lenders and contractors.

Scrawled across a whiteboard in Mr. Spicer’s office, just past three Red Bull-quaffing employees who sit in front of double-screen computers searching for property and managing renovations, was a list of 32 new units that were finished or being worked on. That’s the equivalent of a midsize apartment building. Except unlike a midsize apartment building, which could take years of permitting and environmental reviews before construction even started, Mr. Spicer’s projects require about the amount of bureaucracy of a kitchen and bath remodel.

His company bought 5120 Baxter Street for $700,000. He estimates the house would rent for $3,300 a month with a few renovations. Instead he spent about $400,000 building the new units and splitting the house, and believes he will get between $9,000 and $10,000 a month in rent across the property.

That return would increase the property’s value to about $1.7 million. The price would be galling to an aspiring homeowner who might have outbid another family before losing to Mr. Spicer and now feels cheated out of the American dream. But of course the 10 to 12 people who move in are unlikely to think the world would be better off if their homes had remained dirt and only one family lived there. Housing is complicated.

Neighbors for a Better San Diego

A lawn sign opposing additional dwelling units in the neighborhood. Sandy Huffaker for The New York Times

The yard signs have started to appear. This particular one was on Budd Street in Clairemont Mesa, about a 10-minute drive from the house on Baxter Street. When I arrived on the block to ask the neighbors about San Diego’s surge in backyard apartments, one discontented resident became two and two became a half-dozen. Suddenly I was in a semicircle absorbing dark prognostications from homeowners in shorts and gardening clothes, along with a grandmother holding a baby.

“It doesn’t fit.” “It’s adding people.” “We don’t want that here.” “There’s other places for that.” “We just want to keep our neighborhood like it is.” “They want to push us out and tear our houses down.” “Parking.” “Parking.” “Parking.”

The signs were supplied by Neighbors for a Better San Diego, a nonprofit that has called on the city to rescind its expanded A.D.U. rules. It’s tricky politics, requiring legislators to grapple with the housing crisis by planning for more units while also dealing with blowback from the constituents who vote for them in the present.

Trying to thread this line, Sean Elo-Rivera, a 38-year-old San Diego councilman, recently introduced a series of proposals that would levy infrastructure fees on A.D.U. developers like Mr. Spicer, limit how much on-street parking their residents could use, and lower the income threshold that developers needed to meet to qualify for the city’s density bonus program. But during a walk around his neighborhood he reiterated his support for higher density and illustrated this fact by stopping in front of a six-unit apartment building on a street of single-family houses.

“This is the nightmare scenario for a lot of the more vocal opponents,” he said.

He noted the building was where he lived in a one-bedroom with his wife.

Housing politics are nonpartisan: The term NIMBY, short for “not in my backyard,” applies to Democrats as well as Republicans. Interviews with more than a dozen A.D.U. opponents throughout the city returned an ideologically scattered mix of complaints with a crosscurrent of motivations.

They don’t want low-income housing in their neighborhood and also want new units to be more affordable. Some want backyards to remain open. Others are building A.D.U.s but think adding more than one unit is too much. One complained about Airbnb rentals. Another complained that noise from a neighboring A.D.U. had made it harder to rent his Airbnb. They were fervently for, and against, the attempted recall of Governor Newsom.

If there is one thing they all seem to agree on, a villain whose actions elicit so much rage that it unites this disparate group, it’s that Christian Spicer is the bad guy here.

“My biggest fear is developers are pricing everybody out of the market,” said Pattie Estrada, a 59-year-old commercial loan processor.

Ms. Estrada was part of the Budd Street scrum and has lived on the block for 30 years. As we walked away from her angry neighbors, she told me that her oldest daughter lived in a manufactured home with her husband and 3-year-old and wants to upgrade to a house. The daughter’s family can’t afford Clairemont when houses are going for $850,000.

A few doors away stood a house with a For Sale sign. Ms. Estrada pointed to it and said she wanted to help her daughter buy it, but was worried an investor would outbid them. This would be a huge disappointment, because the house had a yard with the potential to help her solve two problems at once.

“My daughter will be 30, and I have another daughter who is 21 — she still lives at home,” Ms. Estrada said. “I’m thinking we can do an A.D.U. back there for her. She can have her own little place, too.”

‘It’s All About the Money’

On Pattie Estrada’s block in Clairemont, a number of homeowners already have their adult children living in backyard apartments. Sandy Huffaker for The New York Times

So: Pattie Estrada is worried about developers turning single-family houses into multiple units, but on account of the rising cost of housing is doing the same herself. It seems like a contradiction, but within it lies a subtle but profound shift.

Hatred of real estate developers (save for the one who built your home) is practically a condition of living in California. And every era has its growth skeptics. In the mid-1950s, when Clairemont had 7,000 homes and 5,000 more under construction or in planning, a local illustrator named Theodor Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, drew a series of anti-development cartoons with names like “Whither California?” and pictures of hills choked with homes.

But Ms. Estrada isn’t precisely complaining about growth — she’s mad that investors like Mr. Spicer have become a source of competition that could crowd out families that might develop land for one another.

“If you want to build your garage into a A.D.U. or you want to put one in your backyard — God bless you, that’s awesome,” she said. “But I know these developers, and it’s all about profit. It’s all about the money.”

For three-quarters of a century, the California dream has been synonymous with a house like 5120 Baxter and its cousins in the postwar suburbs. But there was an earlier version of California living, one where urban neighborhoods had apartments next to houses and suburbs had boarding units and small-scale farms that families used for food and extra income, making their property work for them. The state’s housing future is starting to look like that homestead past.

On Ms. Estrada’s block, a number of homeowners already have their adult children living in backyard apartments, along with aunts and uncles in converted garages. Units without permits are a common enough sight in Clairemont that Mr. Logue, the teacher on Baxter Street, called it “the Clairemont remodel.”

None of this is atypical: California has long had some of the most overcrowded homes in the country, and researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles, estimate that the Los Angeles metropolitan area has over 300,000 unpermitted units. Some were built for income. Others were built for family. Whatever the reason, they are now a crucial piece of the housing stock and home to a city’s worth of people. Legalized A.D.U.s are just a higher-end version of the same idea.This theme shows up in surveys of A.D.U. rents, which are affordable compared with similarly sized units in the area. It’s not because they are undesirable. It’s that a lot of them are discounted for friends and free to family.

Ms. Estrada didn’t get the house down the street. Another family bought it. No matter: She plans to employ the state’s new A.D.U. laws to develop her own property to the max, adding a 1,200-square-foot apartment above her house and making the garage a one-bedroom. Her parents will live there. Her adult daughters will live there. She has already hired an architect.

“A house for me was security for me and my husband,” she said. “And now we’re going to use it to secure our daughters’ future.”

The model homes advertised in the Clairemont Villas brochure are still standing, wrapped around a corner of Clairemont Drive. Fading white picket fences enclose the front yards. On a recent afternoon, one had its garage door raised. Inside were crates of canned goods and produce along with a half-dozen shopping carts loaded with bags of groceries. Nobody was living inside: The dream house is now a food bank.

Alain Delaquérière contributed research.

Conor Dougherty is an economics reporter and the author of “Golden Gates: Fighting for Housing in America.” His work focuses on the West Coast, real estate and wage stagnation among U.S. workers.